This past weekend, the Columbus Blue Jackets hosted the inaugural CBJHAC, a hockey analytics conference. The event, held at Nationwide Arena, featured presentations and panels from many of the game's most renowned names in the sport's growing analytics community, NHL employees, data-collection companies, hobbyists, and media.

SB Nation's The Cannon provided a nice breakdown of the event, which culminated on Saturday evening with conference-goers attending the Blue Jackets game against the visiting Colorado Avalanche. The entire day was professionally recorded by the Blue Jackets. Here's the link to watch any/all of the full eight-plus hour day.

On Sunday, the conference finished in earnest, with a data contest hosted by the Blue Jackets that was judged by personnel from seven NHL teams: Columbus, Colorado, St. Louis Blues, New York Rangers, New Jersey Devils, Vegas Golden Knights, and Seattle Kraken. A brief overview: competitors that successfully navigated a data module were given AHL player tracking data provided by Sportlogiq from the 2018-19 season and tasked with finding and presenting a creative and actionable solution to the types of problems NHL teams are confronted with every day.

Brandon Nazek, my teammate for the competition, and I were among those selected to present a lightning talk at the data contest. While we were disappointed to not be among the finalists, we were grateful to have a platform to share our findings. Once again, thanks to the Blue Jackets organization, The Athletic's Alison Lukan, and SportslogIQ. Below is our summary, as well as a link with our slide deck (bottom of the article).

Congrats to the #CBJHAC data contest winners

— Alison (@AlisonL) February 9, 2020

1@NathandeLara_

2 @AlexNovet

3 @sprech

And acknowledgement and thanks to all finalists for their great work!!! pic.twitter.com/Zc0yfqebAm

It has long been standard operating procedure for players to play on their ‘strong-side’; that is, right-handed players are significantly more likely to play right defense/right-wing than their left-handed counterparts. The Sportlogiq data provided showed that 89% of wingers played on their strong-side. This project’s intent was to better understand if there was a benefit to wingers playing on their strong-side as opposed to their ‘off-side’ in terms of transition defense as well as transition offense. Has unchallenged conventional wisdom led the hockey community to miss a key edge in roster construction?

Simply put, should wingers be playing on their strong or off-side?

The significance of handedness is a sparsely explored topic in publicly available research, particularly related to wingers. The research in this project was split into two key areas of focus: defensive zone exits and offensive zone entries (Note: all figures/data herein are at even-strength). Pertinent metrics for each area were calculated and a comprehensive snapshot was developed that a coach or manager could utilize to make roster and in-game strategical decisions.

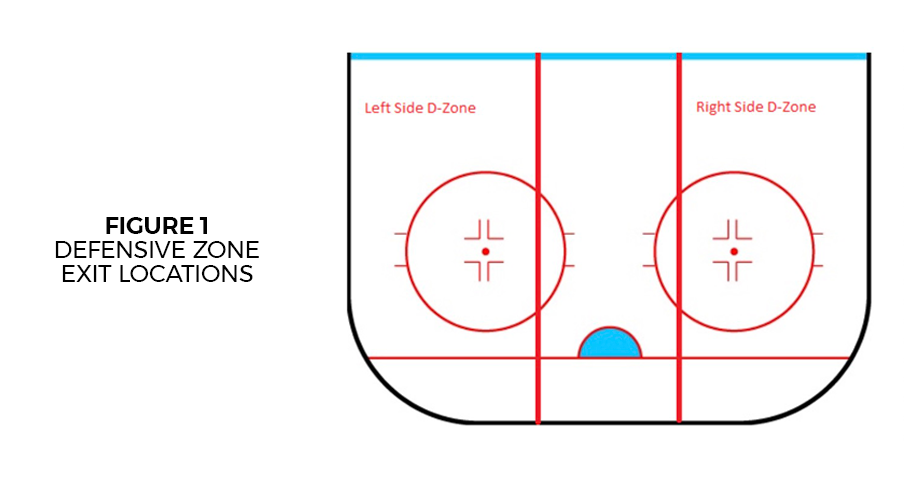

A coach or manager would not play a player on their off-wing if data shows that off-wing players perform poorly compared to strong wing players in terms of defensive transition. Defensive zone metrics were calculated on the basis of zone exits, both controlled and uncontrolled, for both sides of the ice grouped by handedness. A successful defensive zone possession was defined as a successful loose puck recovery (LPR) or successful pass reception within specified areas on the left or right side of the defensive zone. Figure 1 provides a visual representation of these areas. Table 1 shows successful possession percentages by side of the ice and handedness along with a variety of other zone exit metrics.

On both sides of the defensive zone, both left-handed and right-handed wingers show similar successful possessions percentages at roughly 86%. Additionally, handedness does not appear to be a factor in terms of controlled exit percentage on either side of the ice. A successful controlled exit was defined as an event where a player carried the puck outside of the blue line successfully or passed the puck with a successful reception by a teammate outside of the zone. On both sides of the defensive zone, off-side and strong-side wingers had similar controlled exit percentages. This research indicates that handedness is not a factor in defensive zone transition play, and playing the off-side does not suggest any defensive liability.

These findings were at odds with the general consensus of the hockey community. Off-side wingers will typically receive a breakout pass on their backhand, which puts that player in a more difficult situation than a strong-side winger, who will catch a breakout pass on their forehand and be ready to make the next play with their forehand leading into the middle of the ice. Players on their off-wing will have to “open up” to the middle of the ice to make a pass on their forehand. In that vein, Domenic Galamini’s analysis of handedness among defensemen found that teams are “justified in their pursuit of a balanced shooting d-corps defense pairings” (in terms of 5v5 shot differential & 5v5 expected goal differential).

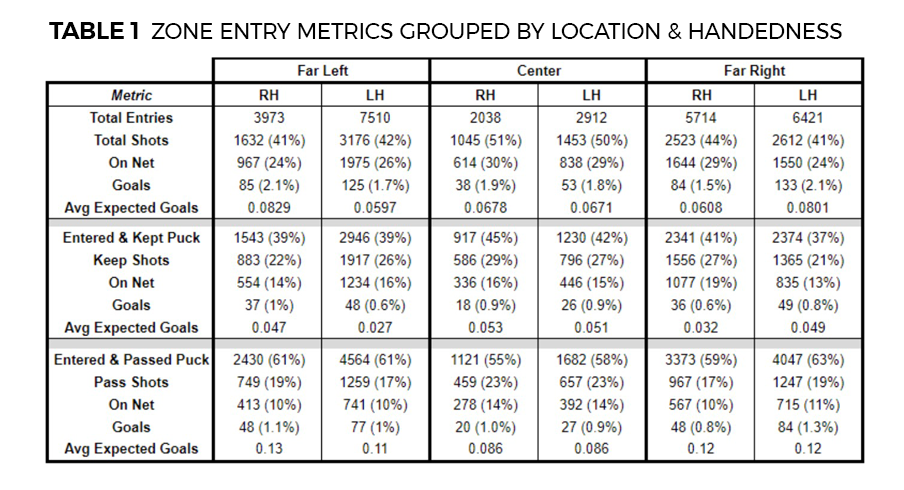

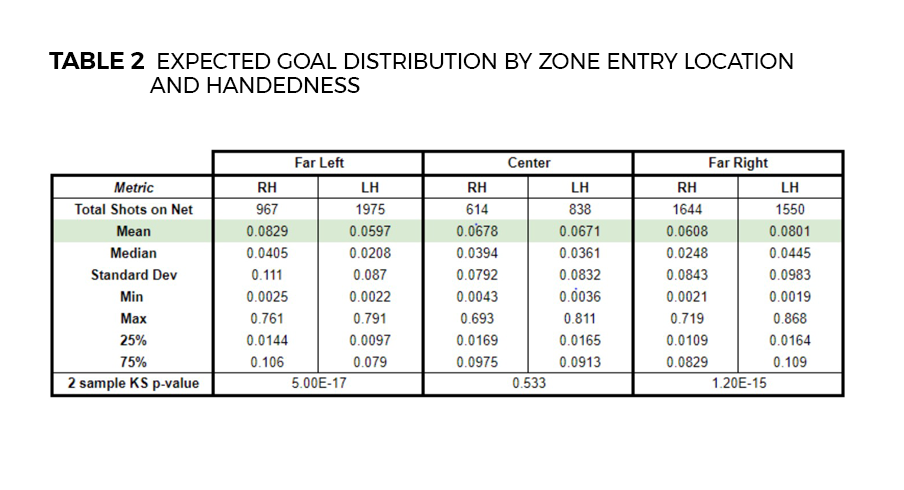

Next, offensive opportunity resulting from zone entries was calculated by segregating zone entry location and handedness. Once a player enters the zone, they can either keep or pass the puck. Keep plays, pass plays, and total plays were evaluated as to whether they resulted in a shot, as well as the expectation and result of that shot. Table 2 shows metrics such as shots on net, goal percentage, and expected goals for these groupings. These metrics indicate that players who enter the zone on their off-wing generate both a higher goal percentage as a proportion of total zone entries as well as higher expected goals average for shots on net. This advantage is attributed to plays where the entering player kept the puck and took a shot.

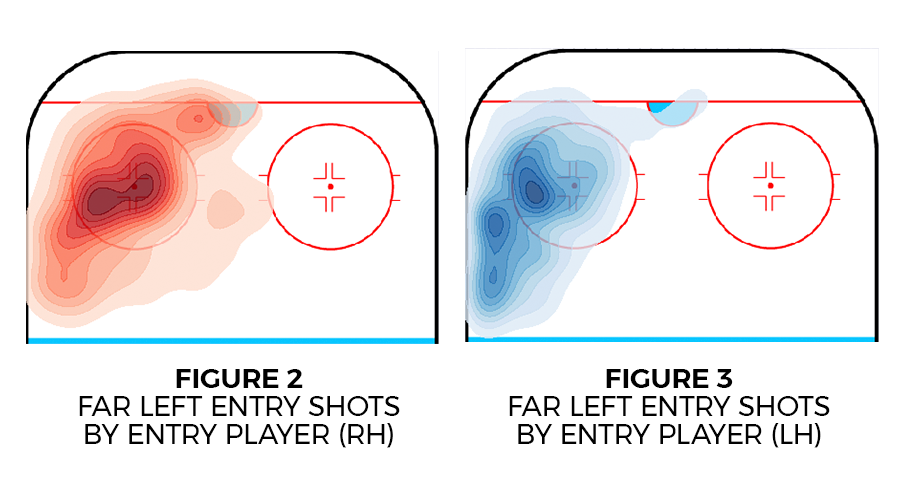

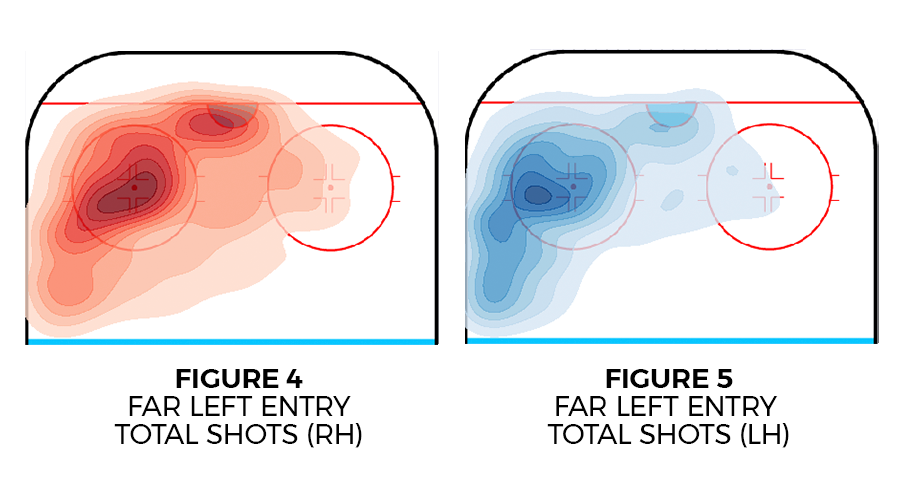

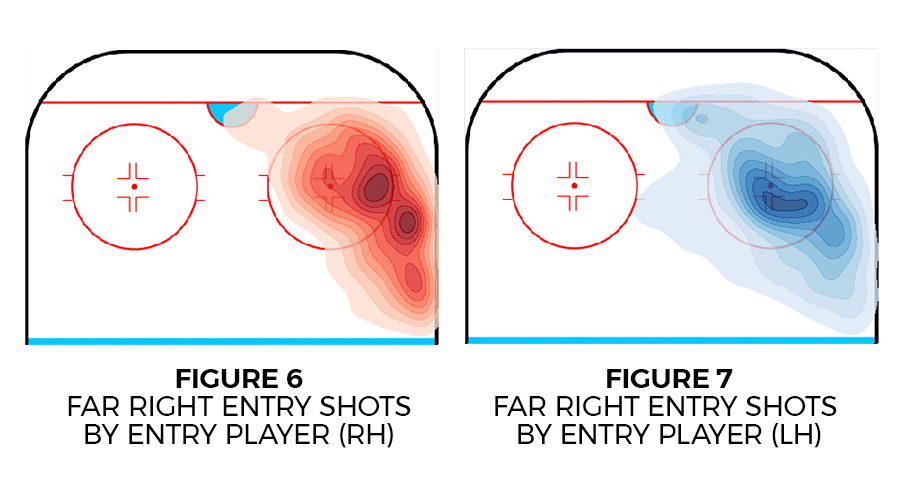

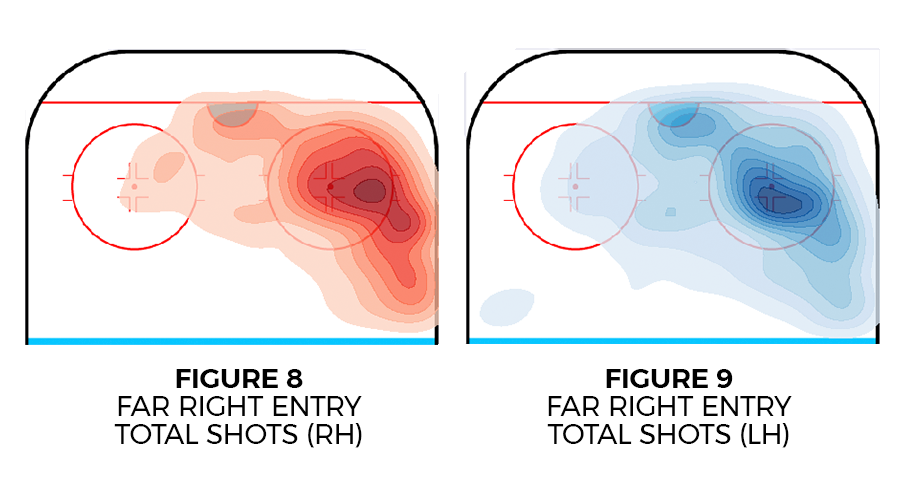

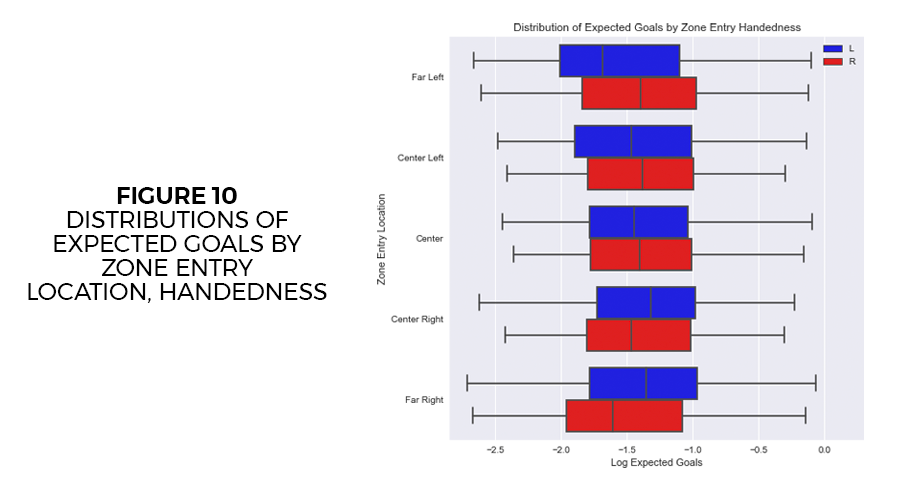

These results make intuitive sense. As a right-wing approaches the opponent’s goal on the right side of the offensive zone, this player is effectively taking away his/her own shooting angle, as the puck is closer to the corner than the slot. The right-handedness works against the player. On the contrary, a left-handed player on the right side of the ice has the puck in a more desirable shooting angle in the middle of the ice, thus creating higher-danger scoring chances. Figures 2-9 show visual representations of shot quality and density by handedness and zone entry location. Figure 10 shows that on a relative basis, the shots generated when a player enters the zone on their off-wing are of higher quality in terms of expected goals compared to entry on their strong-side. Table 2 supports this conclusion showing a higher mean, median, 25th percentile, and 75th percentile of expected goals for shots resulting from zone entries by off-side players. Figure 10 shows visually, and Table 2 shows numerically, that zone entry through the center of ice results in similar offensive opportunities regardless of handedness.

The research in this paper leads to a recommendation to coaches and decision-makers to challenge the status quo of playing wingers on their strong-side as the default setting. The metrics in this paper provide a strong argument that there is no defensive zone liability in playing a winger on the off-wing. Offensively, the metrics and graphics presented herein show that entering the offensive zone on one’s off-side leads to more favorable outcomes, in terms of expected and actual scoring percentage.

There are several limitations to this research. First, it’s likely not a coincidence that some of the most dangerous wingers in the NHL (Patrick Kane, Alexander Ovechkin, Artemi Panarin, Mikko Rantanen, etc.) play on their off-wing. Their coaches clearly feel confident that these elite players can play on their backhand in the defensive zone while also understanding that their offhandedness will put them in the best position to succeed in the offensive zone. Perhaps coaches are only willing to play the truly elite wingers on their off-wing, convinced that their offensive output will trump any potential defensive limitations.

Although Figures 2-9 indicate that shooting from worse angles result in an exceedingly low expected goal percentage for a single shot (on face value), the prevailing ‘no shot is a bad shot’ mantra could still hold true with regards to rebounds and other chaos that results from a bad-angle shot, which was not included in this study. Future areas to consider would be a team-by-team or player-by-player analysis. Comparing individual player performances on various sides of the ice could be insightful for roster construction. Additionally, while this analysis focused on even-strength play, it is likely that offensive metrics would be even more supportive of playing the off-wing in power-play situations, where time and space is more plentiful.

In addition, our slide deck can be found here.